One day in Cleveland (Part 2)

Visiting University Circle and surroundings

This continues and concludes my last post:

Here’s a map for the 2 posts on Cleveland.

University Circle

Early in the afternoon, a shuttle took me from downtown Cleveland to University Circle.

“University” in University Circle refers to Case Western Reserve University1. The neighborhood contains the university as well as a park with museums and other cultural institutions like the (world-class) Cleveland Orchestra’s Severance Hall.

The setup reminded me a little of Washington University in St. Louis (my undergrad school), with Forest Park next to it. But University Circle is a lot less park than Forest Park, and the Case Western Reserve campus seems more connected to the rest of the city.

On the way to this neighborhood, I remembered something. The Michelson-Morley experiment happened here in 1887. This is the experiment that tried to find a difference in the speed of light depending on its direction. The theory was that Earth must be moving through “luminiferous ether”, supposedly the medium that carries light, so the speed of light must change depending on whether it’s traveling along, against, or across the flow of ether.

The experiment failed to find this difference in the speed of light traveling in different directions. There’s some dispute over how much the result of this specific experiment influenced Einstein as he developed his theory of relativity, but this was one of the experiments that buried the ether theory.

Albert Michelson was a professor at the Case School of Applied Science, and Edward Morley was a professor at Western Reserve University. These 2 schools combined to form Case Western Reserve University.

So yes, there’s things like historical markers here.

As you might expect for an area with a prestigious college, the whole neighborhood is quite walkable. Unfortunately, it started raining so I made a pit stop at Blue Sky Brews, another very good coffeeshop, and read another chapter of Jane Jacobs.

I’ll have a section about her book below, and coincidentally, Tomas Pueyo, whom I mentioned in the footnotes to Part 1, just wrote a post heavily referencing Jane Jacobs:

Around University Circle

I explored the wider area after the rain stopped, and this is truly a fascinating place.

The eastern part of University Circle is Little Italy, where there’s lots of Italian food.

If you go past Little Italy, there’s a steep hill that goes up to the suburb of Cleveland Heights. It’s so steep that not many roads go up the hill, which seems to lead to heavy traffic during rush hour.

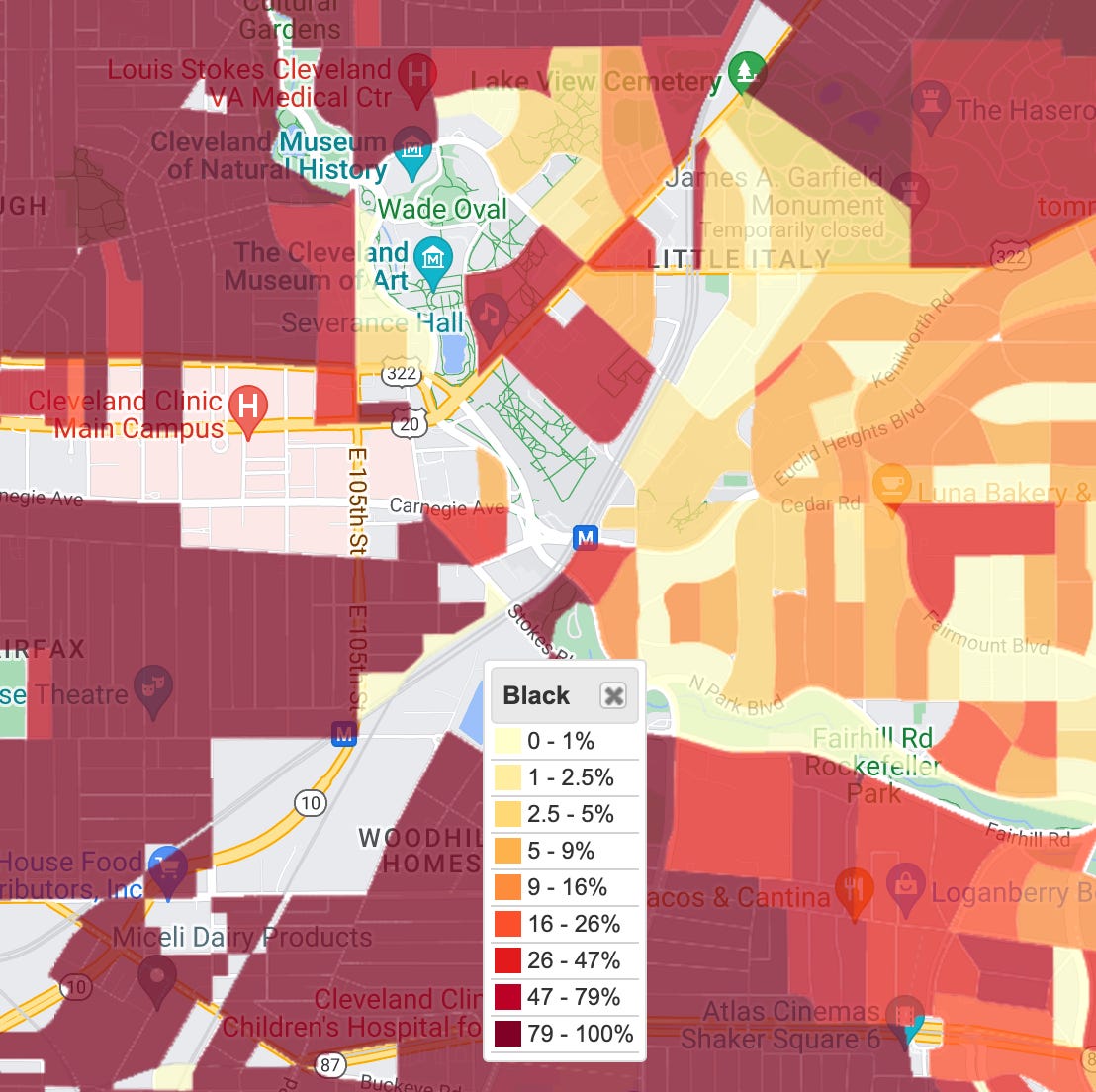

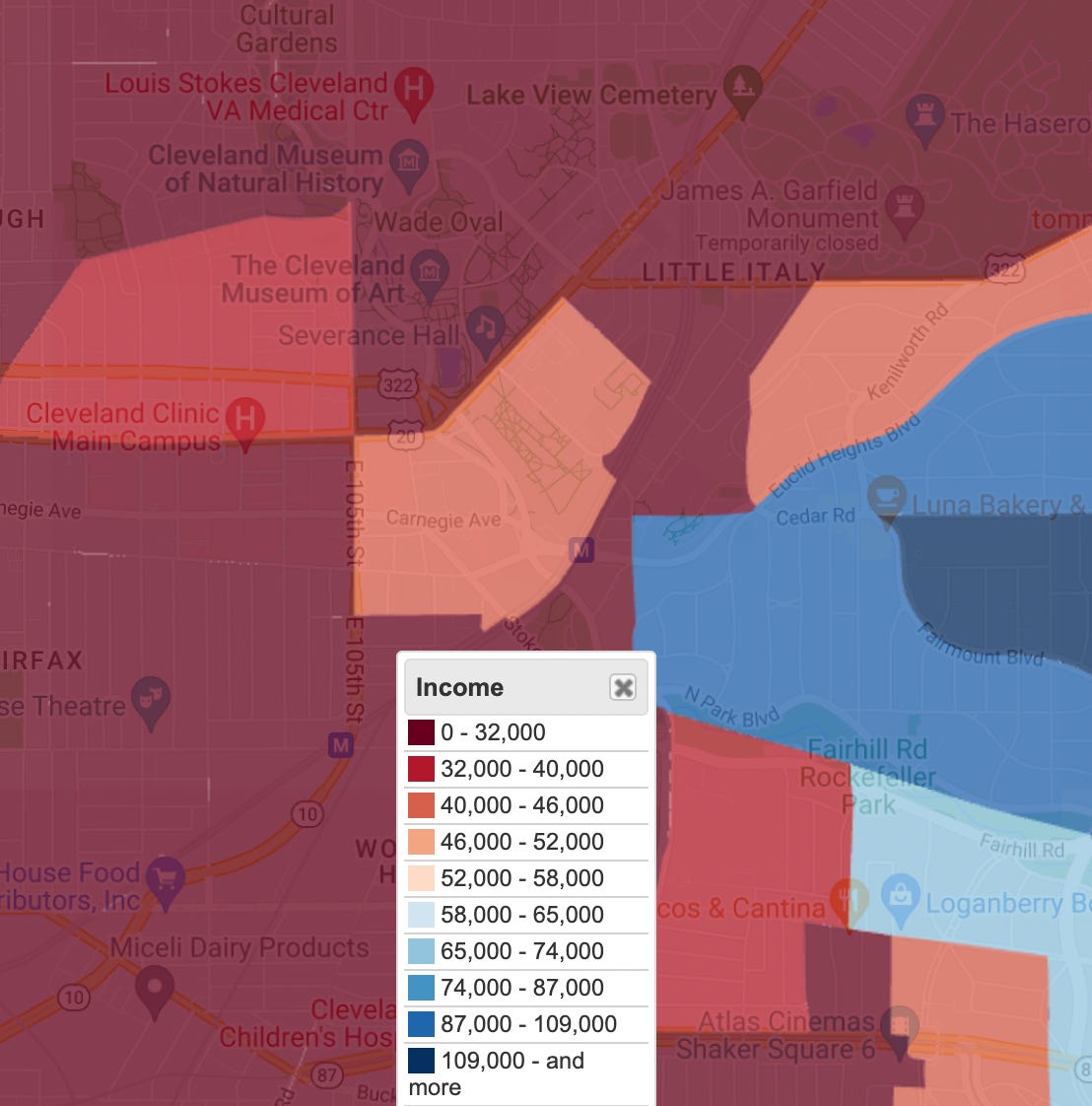

To the west of University Circle, there is the Cleveland Clinic, an excellent hospital, and 2 neighborhoods (Hough and Fairfax) whose residents are overwhelmingly black and poor.

It’s worth noting that the areas right around the college have low median household income because students live there. If you ignore those, there’s a stark contrast between many census tracts in Hough and Fairfax with median incomes of <$20k and ones in Cleveland Heights with >$80k. (Go to the link for clickable maps.)

I occasionally encounter people who seem to think that racial segregation is a uniquely Southern thing, and it’s maps like these that make me wonder if they are paying any attention.

“The curse of border vacuums”

During the morning in downtown Cleveland, I had read Chapter 14 of The Death and Life of Great American Cities by Jane Jacobs, called “The curse of border vacuums”.

It’s about how borders between 2 different parts of cities can be bad for the immediately neighboring areas. The quintessential example is railroad tracks, where you tend to find dead zones, but this applies to other borders as well.

Furthermore, we can see that the same sort of blight typically occurs along city waterfronts. Usually it is worse and there is more of it along the waterfronts than along the tracks. Yet waterfronts are not inherently noisy, dirty or disagreeable environments.

It is curious, too, how frequently the immediate neighborhoods surrounding big-city university campuses, City Beautiful civic centers, large hospital grounds, and even large parks, are extraordinarily blight-prone, and how frequently, even when they are not smitten by physical decay, they are apt to be stagnant—a condition that precedes decay.

The problem with borders is that people tend to not cross the border, whether because it’s physically impossible or difficult, or because they don’t have a reason to cross over to the other side. That means the streets going into the border are basically dead ends for them, and most people don’t go to dead ends unless there’s a really good reason.

This was a theme I kept seeing on this day in Cleveland. I pointed out one example in Part 1, which is the freeway between the lakefront and the rest of downtown. There also happens to be a train track right next to that freeway, so the dead zone is even bigger.

In the University Circle area, you also see the same thing with train tracks. One problem here seems to be that there are 3 sets of tracks, as you can see on the map above. This makes overpasses and underpasses longer, making it harder for people to cross the border.

Then there’s the Cleveland Clinic. I didn’t go too far into the hospital grounds, but what I saw was a lot of large buildings surrounded by large roads. So it didn’t seem too inviting for people in the surrounding area to go in and out.

Now, I’m not trying to argue that if the hospital did a better job, Fairfax wouldn’t be a struggling neighborhood. Segregation, white flight, and deindustrialization are forces that are bigger than even a very well-funded hospital. But I’ve often found big hospital complexes to be very car-friendly, which makes it not great to be in the surrounding area.

I would argue for eliminating the downtown freeway, but train tracks (assuming they’re getting used) and hospitals are good things to have in a city. So the way forward is not to eliminate the border but to encourage people to cross it. One of Jacobs’s suggestions is to put things that the public can use at the outer edges of campus2. This would attract more people to the area just outside the campus as well, because now non-affiliated people are going through the border, rather than staying off the campus and usually not going up to the border.

Wrapping up

In terms of eating in this area, Mayfield Road in Little Italy is where you would go for classic Italian-American fare. There’s a lot of people trying to get that and a lot of businesses lining up to provide that. If you want something less familiar, you have a better shot by straying into side streets.

(Translation: I should’ve taken my own advice and tried something like Algebra Tea House or Tutto Carne.)

Amazingly, the Cleveland Museum of Art is open until 9 p.m. on Wednesdays. So that’s where I spent my time after dinner, until my ride back to Kent. Reiterating what I wrote in Part 1, Cleveland was a big and wealthy city until the middle of the 20th century, and that really shows in an art museum.

Given the time constraints, I’m pretty happy with how much I got to see. After all, I did write 2 posts about 1 day3. Yet it was mostly only 2 small areas in a city that seems to have many pockets of interesting stuff, and I got through maybe a quarter of things that were recommended to me. I could easily fill 2 or 3 more days there, without doing any more homework. Cleveland may not be a popular tourist destination, but when there’s millions of people, there’s bound to be many things to discover.

What I’m listening to now

This is a previously unreleased live recording of Nina Simone’s performance at the 1966 Newport Jazz Festival. I’ve listened to enough Nina Simone that I’m familiar with most of the material here, but I still found new things.

I like the studio version of “You’ve Got To Learn” on the album I Put a Spell on You. The live version here is less orchestrated and much looser, as you’d expect, and just as dramatic4.

The best-known version of the civil rights protest song “Mississippi Goddam”, from her 1964 Carnegie Hall performance, is one of the most remarkable live recordings I know. The audience was expecting a light, playful tune based on how it starts, but the song takes a turn. This is one where the original could not be topped, if only because the audience was more ready for the song in 1966.

I must have heard “Blues for Mama” on the Nina Simone Sings the Blues album, but I didn’t take much note of it. On the new album, the song is highlighted with an intro, and yes, the live version is better.

Or probably to be more precise, it refers to the parent institutions.

Did you know that the Western Reserve refers the piece of land directly to the west of, and claimed by, Connecticut? This included Cleveland, and for that matter, what later became Chicago.

This suggestion was for universities, but it’s pretty obviously applicable to hospitals.

Please don’t ask me to compare the amount of time I spent writing about being in Cleveland to the amount of time I spent being in Cleveland.

I just found out that this song is originally a chanson by Charles Aznavour called “Il faut savoir“.

A question for French speakers out there (resolved—see below): The English lyrics “You’ve got to learn to leave the table/ When love’s no longer being served“ is the translation of “Il faut savoir quitter la table/ Lorsque l’amour est desservi“. Superficially (i.e. with machine translation and my limited French knowledge), this seems like the oppposite, but my guess is that these actually mean the same thing because “l’amour est desservi” means that love has been—and has finished being—served. Is that right?

Answer: desservir was machine translated as “to serve”, but it actually means to clear away something, like a table. So with this understanding of the word, the lyrics mean much the same thing.