More tips on having good food in Japan

I stand by my konbini and depachika post, but there's obviously more

Short updates:

We’re probably going to the Chicago Jazz Festival, and we’ll try to make it to another Millennium Park concert, just before that. Anjélique Kidjo, one of the biggest African singers—whom I’ve seen covering Talking Heads at Ravinia—is playing with Yo-Yo Ma on 8/26.

We’re planning on going to New York in October. More to come on this, I’m sure.

My biggest quick tips for finding interesting food in Japan are going to a konbini (convenience store) and a depachika (department store basement), as I wrote in this post almost 3 years ago:

There’s obviously many layers to understanding food in Japan—or anywhere—so there’s a lot more I can say. I’ve thought a bit more about this during my Japan trip in June, and I was able to distill a lot of what I want to say into the following 3 points:

It’s easy and cheap to get A-minus food in Japan.

Japanese people don’t eat sushi every day.

Seek out regional specialties.

It’s easy and cheap to get A-minus food

If you go to a random restaurant in the US, especially in touristy areas, you’re likely to get very predictable menus consisting of very mediocre food. I claim that this is not the case in Japan, which you could probably guess from how you can get decent food at 7-Eleven. The default quality—I sometimes call it the replacement level1—of restaurant food is higher in Japan. Not everything is exceptional food, obviously, but you will usually find good recipes executed well. It’s not A or A-plus, but just below that.

One implication of this is, it might be better to find, say, a tonkatsu place near where you happen to be, rather than trying to figure out where “the best tonkatsu in Tokyo” is2. This is especially true in Tokyo, a city that is as dense as New York and as spread out as LA. I’ve seen advice online saying you should book restaurants in advance when you visit Japan, and I disagree strongly. The only exception is if you’re really, really sure you want to go to a particular very popular or exclusive restaurant.

My real advice is to just find any old place and try it, but if you feel that’s too risky, Tabelog is the most reliable food review site in Japan. Unlike Google Maps or TripAdvisor, most of the ratings come from locals. The main thing to keep in mind is that its reviewers are extremely tough—3 stars (out of 5) means you’re pretty good, 3.5 is really good, 4 is a rare achievement.

Japanese people don’t eat sushi every day

I’ve had multiple people in America ask me if Japanese people eat sushi every day. The most recent was our driver taking us home from O’Hare after the Japan trip. Even after I explained how there are many, many Japanese dishes that Japanese people eat everyday that aren’t sushi—and that, in fact, most Japanese people only eat sushi on occasion—he still seemed convinced that sushi was the best thing to have in Japan.

Let me talk about this in a different way. If you’re in a big city in the US, there are 2 kinds of Japanese food that you could often find at the replacement level in Japan (i.e. A-minus) or even higher: sushi and ramen3.

In Japan, you’ll find that lots of restaurants specialize in a narrow range of Japanese dishes. It could be soba, udon, unagi (eel), yakitori (grilled chicken skewers), tonkatsu—actually I’m just reading off some of the categories on Tabelog—and each of these specialities are as worthy of mastery by cooks and exploration by eaters as sushi and ramen.

If you love the best sushi places in your city, I don’t want to stop you from trying to find even better ones in Japan. But if you want to have an experience that’s hard to find outside of Japan, you should really be going for all the other things that you’re not that familiar with.

but also, there’s sushi that’s hard to find outside Japan

When you say “sushi” in the US, most people would think of nigiri, or more likely, maki (rolls). But there are other types of sushi in Japan that you don’t see often in the US.

Chirashi, or chirashizushi4, or “scattered” sushi, is a dish where various pieces of seafood and other ingredients are placed on top of sushi rice. I remember chirashi being served at home when I was growing up, probably made by a grandma, so it’s a kind of sushi that home cooks can manage, similar to maki. In Chicago, you can find it at Gene Kato’s Momotaro and Itoko, and restaurants catering to Japanese people, especially in the suburbs. We did get a chirashi bento in Okayama this trip, but I shamefully failed to get a photo. The photo below is from Itoko, and it’s way more precious than your regular chirashi in Japan.

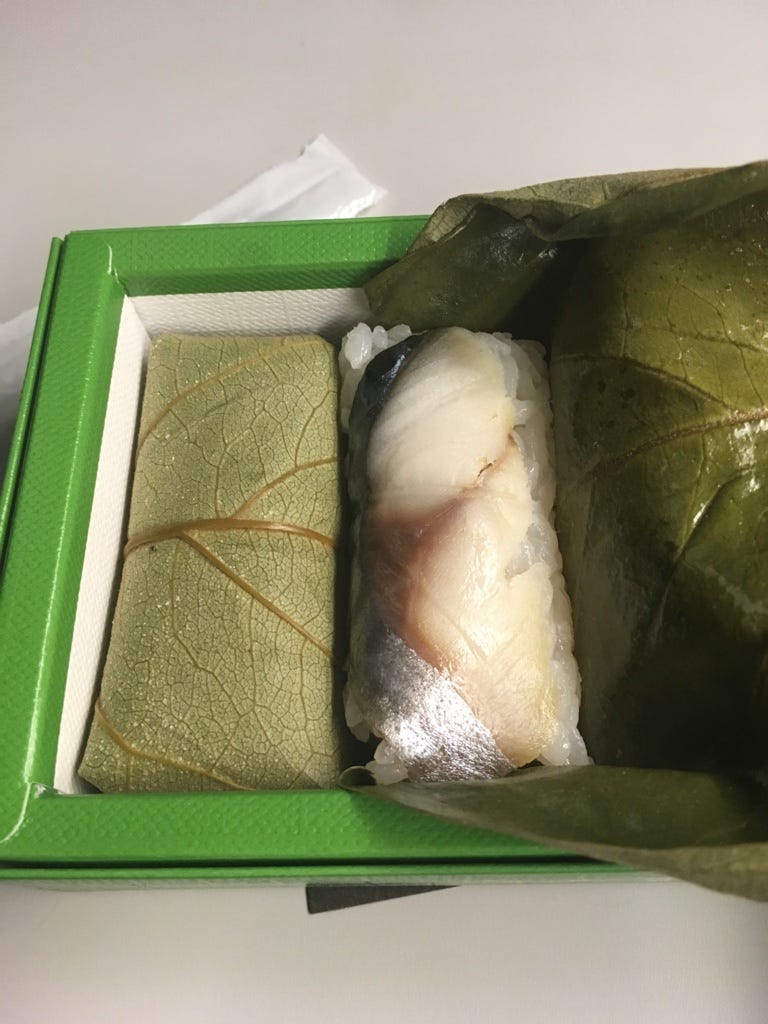

The other common one is oshizushi, or “pressed” sushi. For this one, the cook would put the topping on rice, then press the whole thing into shape using a rectangular box. This is a great option for ekiben (bento boxes you can buy at train stations or on express trains).

I didn’t think pressed sushi was available in Chicago until recently, when I found 2 menu items at Cocoro in River North.

Seek out regional specialties

The best dish I had this trip was udon in Kagawa.

This was at a serufu—”self”, as in “self-service”—udon restaurant, meaning you order the noodles first (in a hot broth, cold and plain, in curry, etc.), you add the toppings yourself, then pay at the end depending on what you put on top of the udon. So it’s a no-frills place, but even at fancier places, udon in Kagawa is a simple joy. The noodles are famously firm, almost al dente, and your soup or dipping sauce provide satisfying umami. Kagawa is so serious about udon that our hotel had udon as part of the breakfast buffet. I’m not sure if I’ve seen that anywhere else.

Wherever you are in Japan, you’ll find regional specialties, and it’s almost always worth trying them.

Osaka famously has a few.

Okonomiyaki is a savory pancake cooked on a griddle, and Chicago has a great exponent of this dish in Gaijin. It’s much cheaper in Osaka. Takoyaki (octopus ball) is now a pretty common dish at Japanese restaurants in the US, but you’ll find better versions in Osaka.

One Osaka specialty that I’ve never seen in the US is kushikatsu, or deep-fried skewers. You dip the skewers in dipping sauces to enjoy. You can make this look fancy but it’s obviously street food.

What I’m listening to now

I’m going to talk about Switcheroo, the LA-based artist Gelli Haha’s debut album. It’s indie electropop, with quite a bit of weird stuff mixed in there.

The best track is “Bounce House”, a distillation of fun. This is as busy as a song can be and still be perfect. The music video is also great.

The weirdest track is “Piss Artist”, where a narrator recounts a drunken party incident. The first half of the album is stronger, but the whole album is a lot of fun.

Sports nerds know what I’m talking about.

This was a totally made-up example, and it turns out that there does seem to be a consensus “best tonkatsu in Tokyo”. Tonkatsu Narikura is rated 4.25 on Tabelog, while the 2nd place is rated 3.94. But it’d be very hard to get a reservation at these extremely highly-regarded places.

By the way, I re-read another post with travel tips for Japan after writing this section, and realized how close the food tips were to mine.

In Chicago, all the omakase-only sushi restaurants are hopefully better than a random sushi place in Japan. Among the a la carte places, Sushi-San definitely makes the cut, and there’s probably a few others.

For ramen, Akahoshi and Monster are clearly above replacement level. There’s a few more that are around replacement level.

In Japanese, the s sound at the beginning of a word becomes a z sound when you put another word in front of it to make a bigger word. The conveyor belt sushi chain Kura Sushi is actually called Kurazushi in Japan.